Making is Connecting

I see/ not see

The art historian James Elkins writes about seeing. He challenges a number of taken-for-granted ideas about sight and vision. Here are three of his big ideas:

(1) Elkins says that a lot of what we call seeing is actually not-seeing – we screen out much that is actually in our scope of vision, because we are unable to process the sheer amount of available visual information. So as we see, we always simultaneously not-see. We are both sighted and blind at the same time.

(2) Elkins suggests that seeing is not simply what happens in the brain ‘inside ‘ us – it is what happens in between our eyes and objects. And this is not empty space but is actually light. Light joins our eyes and the object we are ‘seeing’. We are not separated from the objects we are looking at but are joined to them by and through light.

(3) Elkins maintains that objects look at us. A knife says pick me up. A cookie says eat me. An unused box reminds us of things we haven’t done. The object can resist being noticed, or invite us to notice it.

This is a challenging idea and Elkins proposes a reason for this:

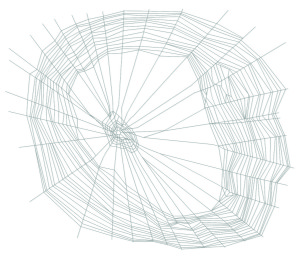

” A psychoanalyst might say that we need to believe that vision is a one-way street and that objects are just the evasive recipients of our gaze in order to maintain the conviction that we are in control of our vision and ourselves. If I think of the world in the ordinary way I am reassured. Everything is mine to command: if I want to see a movie I go and see it. if I want to look at my cat, I look at her. But this implies something darker: that if I resist the idea that objects look back at me and that I am tangled in a web of seeing, then I am also resisting the possibility that I may not be the autonomous, independent, stable self that I claim I am. I may not be coming to terms with the thought that I need these reciprocal gazes in order to go out and be myself.” (p. 74)

Elkins, James (1996) The object stares back. San Diego: Harvest

Noticing from nothing

‘It is what people ‘know’ they experience when they encounter an artwork, even if they are not always able to say what it is that they know. This knowing ‘non-knowledge’ may open a few of the windows that have been closed by ordinary knowledge. […] This process is not only about what people ‘take away’ from a work of art, but also what they ‘bring forward’ in their experience of it.’

Wonderful Uncertainty, Raqs Media Collective

John Cage composed the piece 4”33 as a composition intended to force an unsuspecting audience to notice; in lieu of actual music each listener would begin to tune in to sounds that surrounded them; consequently each listener’s experience would be completely unique and each individual would, in turn, leave with a different account of the work. Richter composed his Cage series of paintings to similar effect; this is a series of work in which abstraction exists as the catalyst for possibility, the work can be interpreted infinitely. Presenting ‘empty’ work, Cage and by extension Richter as the composers create works in which they themselves do not dictate the listener/viewer’s experience. What the listener/viewer then brings forth or takes becomes wholly engrained in what the work is (at least, in an individual sense). Does one interpret the cracks in the paint or the texture of the canvas? Should one read into the colour or the composition? These questions are left unanswered by both Cage and Richter and thus are only answerable by whoever encounters the work and in what capacity they experience it.

Similarly the scholar’s rock, although it has no known creator, exists and is valued because of the possibilities it poses. The object in it’s abstract nature has the potential to become, or signify, absolutely anything to its viewer. It’s presence, solid and object-like, is in itself far more tangible than the likes of Cage’s 4”33, knowledge particularly regarding the object’s history is not certain at all. The jagged formations and entwining surfaces have been preserved for their thought provoking, mediative qualities and many of them have in fact been titled, on account of their resemblance to other objects. These objects of natural beauty and wonderment have been preserved specifically because their finder (of thousands of years ago) saw the importance to do so; in the first instance they have no solid idea or concrete concept, and exist almost exclusively for the purpose of interpretation. Craig Burnett, who curated Structure & Absence describes the rocks as objects that ‘sustain the play between observation and imagination’.

These processes are involved emphatically with experience and share the notion of learning through noticing and having one’s eyes opened, as opposed to being taught, lectured, or engaged in a didactic process of viewing.

Stickiness

Every Saturday morning when my brother and I were growing up, we’d go to the newsagents to each buy a shiny pack of stickers for our collections. For me it was Top of the Pops and for him it was the Premiership League. He was more dedicated than me and would always stick them in the album provided, whilst I often found places like my desk, my door, my bunk bed, my books, my clothes and occasionally my body to house them. Their stickiness marked my habitat, leaving grey smudges where they had fallen off, slowly peeled away or been replaced; only a few ever remained clinging to where they had been originally stuck.

more than a single event

All manner of research relies on noticing and on being alive and alert to the possibility of the unexpected.

One of the researchers I admire most is Jocelyn Bell Burnett, the physicist. She ‘discovered’ pulsars. She noticed an aberrant signal on a printout from a radio telescope and then eventually, much later and almost serendipitously, noticed another.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-4e93q1NdI

Bell Burnett’s doctoral supervisor won the biggest science prize going for this noticing – and it’s often referred to as the No-Bell as a result.

Sections

“There is a section of the web where she [the female] waits and a separate section for catching prey”.

Is this a model for Noticer?

Waiting and catching as two distinct activities?

With separate domains?

Or is it messier than that?

Hippocrates Tree

“The Tree of Hippocrates is the plane tree (or platane, in Europe) under which, according to the legend, Hippocrates of Kos (considered the father of medicine) taught his pupils the art of medicine. Paul of Tarsus purportedly taught here as well. The Platanus in Kos is an oriental plane (Platanus orientalis), with a crown diameter of about 12 metres, said to be the largest for a plane tree in Europe.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tree_of_Hippocrates

Disruptions

Thinking about interruptions/distractions reminds me of notions of ‘the event’ which I am thinking about a lot at the moment for my MA writing.

Dennis Atkinson explains

For Badiou an event is a radical disruption that leads to a subsequent truth procedure which reconfigures the existing knowledge frameworks, practices and values of a social context (2012: 9)

So it is though a commotion causing rupture to prior thinking that the subject can reach new truths. Atkinson explains that it is in this state of disruption that one can be led to uncertainty and not knowing, which leads then to an emancipated state of ‘real learning’.

Is it possible to create a pedagogy of the event, keeping focus on radical leaps effecting local and personal disturbances?

Searching Noticing Checking

“But I never liked doing things systematically. Not even my Ph.D. research was done systematically. It was done in a random, haphazard fashion. The more I got on, the more I felt that, really, one can find something only in that way—in the same way in which, say, a dog runs through a field. If you look at a dog following the advice of his nose, he traverses a patch of land in a completely unplottable manner. And he invariably finds what he is looking for. I think that, as I’ve always had dogs, I’ve learned from them how to do this. So you then have a small amount of material and you accumulate things, and it grows, and one thing takes you to another, and you make something out of these haphazardly assembled

W.G Sebald interviewed by Joe Cuomo, 2001

We worked with this text once before and we identified the dog as a kind of frenetic flaneur, a wanderer (see Pat’s recent post, Dérive).

Now, watching my own puppy Lois, I can identify with this text differently. There is a really interesting paradox in her search, one that I think I share…

Lois is searching for what is known, a ball or a rubber chicken but this search is almost constantly interrupted by noticing and being distracted by other unknown or unexpected things: chicken bones, poos, other dogs. This gives rise to what seems to be an almost sadistic confusion of progression and diversion. By the advice of her nose, she is simultaneously excited and frustrated by the stream of information. And added to that, because she’s a pup who is learning the rules, she is intermittently looking back to me to check that she’s doing ok.

The pace might be different but this seems so like being in the studio, so like planning the summer school, so like learning:

Searching Noticing Checking